Acquired Hemophilia-A Mimicking Trauma-induced Coagulopathy in a Young Polytrauma Patient

1Department of Medical and Surgical Critical Care, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

2Careggi University Hospital, Largo Brambilla 1, Florence, Italy

Author and article information

Cite this as

Capponi A. Acquired Hemophilia-A Mimicking Trauma-induced Coagulopathy in a Young Polytrauma Patient. Ann Circ. 2025; 10(1): 007-010. Available from: 10.17352/ac.000026

Copyright License

© 2025 Capponi A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) is a common early complication in major trauma, typically presented with prolonged PT and aPTT. However, isolated or disproportionate aPTT prolongation warrants consideration of alternative diagnoses, such as acquired hemophilia A, a rare autoimmune disorder marked by factor VIII inhibitors and severe bleeding. This case describes a young, previously healthy trauma patient whose presentation mimicked TIC but was ultimately diagnosed with acquired hemophilia A, requiring immunosuppressive therapy and bypassing agents. The case underscores the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis for coagulopathy in trauma settings to ensure timely recognition and appropriate management of rare but life-threatening conditions.

Trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) is a well-recognized, early complication in major trauma, occurring in approximately 25% of severely injured patients and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. TIC is characterized by a complex interplay of tissue injury, shock, endothelial dysfunction, and dysregulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis, leading to impaired hemostasis and a bleeding phenotype in the acute phase. Laboratory diagnosis of TIC often reveals abnormalities in conventional coagulation tests, including prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), decreased fibrinogen, and platelet dysfunction. A diagnostic challenge arises when aPTT is disproportionately prolonged relative to PT in a trauma patient. While TIC can cause mild to moderate prolongation of both PT and aPTT, a marked isolated or disproportionate prolongation of aPTT should prompt consideration of alternative etiologies, such as acquired hemophilia A. Acquired hemophilia A is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by the development of autoantibodies against factor VIII, leading to severe bleeding and isolated aPTT prolongation, which can mimic TIC in the trauma setting.

This case is unique because it describes a young, previously healthy patient who developed hemophilia A shortly after polytrauma, presenting with laboratory and clinical features that closely resemble TIC but requiring a fundamentally different treatment approach—namely, immunosuppression and bypassing agents rather than standard trauma resuscitation and hemostatic support.

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis for coagulopathy in the trauma intensive care unit, especially when laboratory findings are atypical for TIC, thereby increasing clinical awareness and promoting timely recognition and management of rare but critical conditions such as acquired hemophilia A.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old man without prior health issues was brought to the Emergency Department following a high-speed motorcycle crash.

On arrival: Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 13, hypotension (BP 80/40 mmHg), tachycardia, and signs of thoracoabdominal trauma. A positive Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) examination prompted activation of the major trauma protocol.

Prehospital care: Within 3 hours of injury, the patient received tranexamic acid (TXA, 1 g IV) during prehospital resuscitation, along with balanced transfusion support according to major trauma guidelines.

Initial management

Whole-body computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple rib fractures, bilateral pulmonary contusions, a pelvic fracture, and a grade IV liver laceration. The patient received red blood cells, plasma, and platelets, followed by hepatic artery embolization. He was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in critical condition.

Clinical progression

By day 2 (≈ 36 hours post-trauma), hemodynamic stabilization was achieved. At day 3 post-injury (≈ 60–72 hours after the crash), laboratory studies revealed a markedly prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT > 120 s) with normal prothrombin time (PT/INR 1.1), stable platelet count (190 × 10⁹/L), and normal fibrinogen (3.2 g/L).

Clinical bleeding: Spontaneous oozing from intravenous and drain sites began approximately 48–60 hours after trauma, coinciding with aPTT prolongation. Despite prior TXA administration and conventional transfusion therapy, coagulopathy persisted.

Diagnostic ROTEM evaluation

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) was performed to characterize the coagulation disturbance.

Parameter definitions:

- CT (Clotting Time): time from assay start to initial clot formation.

- CFT (Clot Formation Time): time from the first measurable clot to defined firmness

- α-Angle: slope of clot build-up, reflecting fibrin polymerization rate.

- MCF (Maximum Clot Firmness): peak clot strength.

- ML (Maximum Lysis): percentage reduction of MCF, indicating fibrinolysis.

Interpretation

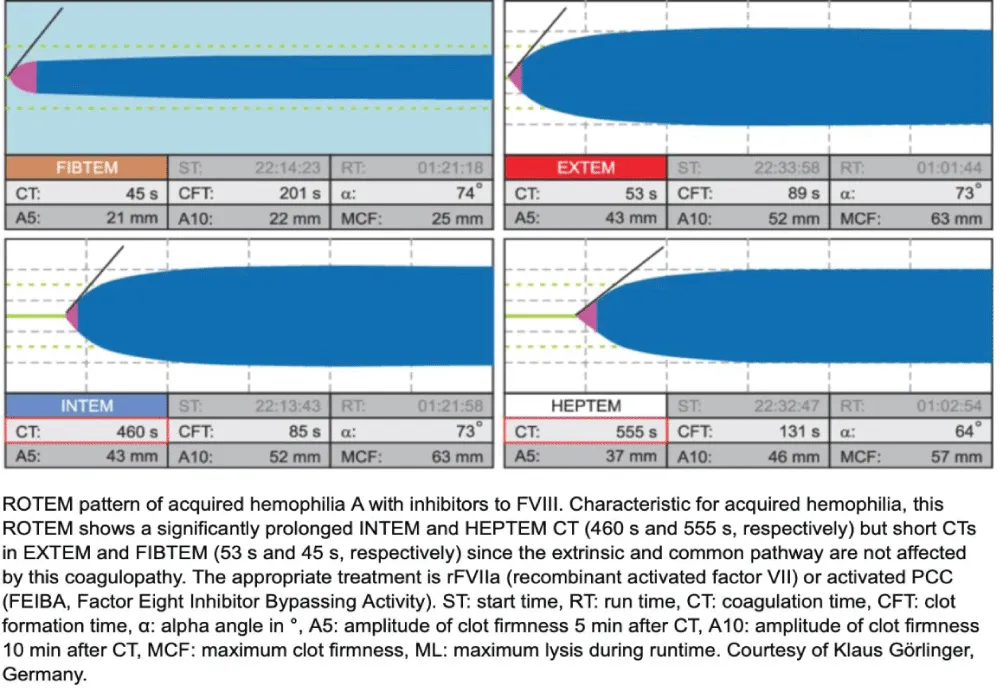

ROTEM showed a markedly prolonged INTEM CT (> 1800 s) with normal EXTEM, FIBTEM, and APTEM, confirming isolated intrinsic pathway dysfunction. Because APTEM did not correct the abnormalities and ML was normal, hyperfibrinolysis was excluded—particularly relevant given prior TXA administration. This pattern was highly suggestive of acquired hemophilia A (factor VIII inhibition) rather than trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC), which usually presents with global derangement and reduced FIBTEM MCF.

Confirmatory testing:

- Factor VIII activity: < 1 %

- Bethesda inhibitor titer: > 5 BU

- → Diagnosis: Acquired hemophilia A.

Treatment and outcome

Immediate therapy with recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) and immunosuppression (methylprednisolone + cyclophosphamide) was initiated.

Hemostasis improved within 24 hours, bleeding ceased, and coagulation parameters normalized.

The patient continued ICU management for trauma-related injuries and was discharged to hematology follow-up on day 15 with full recovery.

Comparison of ROTEM Patterns in Acquired Hemophilia A, Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy, and Hyperfibrinolysis

Interpretive summary

- Timing: Coagulopathy and bleeding onset occurred 48–60 hours post-trauma, despite early TXA administration.

- ROTEM pattern: isolated INTEM CT > 1800 s, preserved EXTEM, FIBTEM, and APTEM, excluding hyperfibrinolysis.

- Diagnosis: Acquired hemophilia A (factor VIII inhibition), confirmed by factor VIII < 1 % and inhibitor > 5 BU.

Discussion

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare but potentially life-threatening autoimmune bleeding disorder characterized by the development of autoantibodies (inhibitors) against coagulation factor VIII (FVIII). These inhibitors neutralize FVIII activity, resulting in an isolated prolongation of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and clinical picture of spontaneous or disproportionate bleeding. Although most cases occur idiopathically or in association with autoimmune diseases, malignancy, or the postpartum state, AHA may also arise secondary to trauma or surgical injury, as illustrated in this case.

In the present patient, coagulopathy developed 48–60 hours after a high-energy trauma, despite hemostatic stabilization and early tranexamic acid (TXA) administration. The isolated, extreme prolongation of the INTEM clotting time (CT > 1800 s) with normal EXTEM, FIBTEM, and APTEM results on ROTEM was incompatible with trauma-induced coagulopathy or hyperfibrinolysis and strongly suggested FVIII inhibition. This was subsequently confirmed by FVIII activity < 1 % and a Bethesda inhibitor titer > 5 BU, establishing the diagnosis of post-traumatic AHA.

Pathogenesis: Post-traumatic versus Idiopathic AHA

The “second-hit” hypothesis proposes that severe tissue injury can trigger autoantibody formation in genetically or immunologically susceptible individuals. Following trauma, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and helper T cells are activated by DAMPs and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ). This inflammatory milieu enhances presentation of FVIII-derived peptides, resulting in activation of autoreactive B cells that produce neutralizing IgG4 antibodies. The process parallels mechanisms described in drug-induced or infection-related autoimmune phenomena.

In this patient, massive tissue damage, cytokine release, and exposure of cryptic FVIII epitopes likely broke immune tolerance, initiating autoantibody production despite no prior autoimmune disease or medication exposure. The temporal association—appearance of bleeding and prolonged aPTT approximately two days after injury—supports this immunologic trigger mechanism.

Clinical relevance

Recognition of post-traumatic AHA is critical because its presentation can mimic trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), but management differs entirely. In TIC, fibrinogen replacement and plasma resuscitation are key; in contrast, AHA requires bypassing agents (e.g., recombinant activated factor VII [rFVIIa] or activated prothrombin complex concentrate [aPCC]) and immunosuppressive therapy to eradicate inhibitors. Early use of ROTEM or other viscoelastic testing enables rapid differentiation: isolated INTEM CT prolongation with preserved EXTEM and FIBTEM profiles should prompt immediate investigation for FVIII inhibitors [1-10].

Conclusion

This case illustrates post-traumatic acquired hemophilia A presenting with delayed-onset bleeding after initial hemostatic stabilization and despite early antifibrinolytic therapy. Trauma likely served as an immunological trigger, leading to FVIII autoantibody formation. Incorporating ROTEM analysis early in unexplained post-trauma coagulopathy can be life-saving by differentiating acquired inhibitors from typical trauma-related coagulopathy and guiding appropriate immunosuppressive and hemostatic therapy.

- Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Advances in the understanding of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Blood. 2016;128(8):1043–52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-636423

- Schöchl H, Nienaber U, Solomon C. ROTEM in trauma: rapid identification of coagulopathy. In: Vincent JL, editor. Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2013. Springer; 2013.

- Iba T, Levy JH, Wada H, Thachil J. Mechanisms and management of coagulopathy of trauma and sepsis. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21(12):3360–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtha.2023.05.028

- Theusinger OM, Wanner GA, Emmert MY, Billeter A, Eismon J, Seifert B, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis diagnosed by ROTEM is associated with higher mortality in severe trauma. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(5):1003–12. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0b013e31822e183f

- Tiede A, Collins P, Knoebl P, Teitel J, Kessler C, Shima M. International recommendations for acquired hemophilia A management. Hamostaseologie. 2024;44(6):466–71.

- Pezeshkpoor B, Sereda N, Becker-Gotot J. Emicizumab for treatment of acquired hemophilia A: consensus recommendations. J Thromb Haemost. 2025;23(1):85–96.

- Huth-Kühne A, Oldenburg J, Knoebl P. Porcine FVIII as first-line treatment in acquired hemophilia A: clinical trial evidence. Blood Adv. 2024;8(22):5896–905.

- Chang R, Cardenas JC, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Advances in the understanding of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Blood. 2016;128(8):1043–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-636423

- Borro M, Tassara R, Paris L, Artom N, Brignone M, Rebella L, et al. Acquired hemophilia A treated with recombinant porcine factor VIII: case report and literature review on its efficacy. Hematol Rep. 2023;15(1):17–22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep15010003

- Webert KE. Pathophysiology and management of bleeding disorders in critical care. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38(7):735–41.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley