Journal of Novel Physiotherapy and Physical Rehabilitation

Technology-guided Precision Training of the Paretic Lower Extremity to Enhance Recovery of Locomotion Post Stroke: A Hypothesis-driven Perspective

Associate Professor Emeritus, University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Author and article information

Cite this as

Alon G. Technology-guided Precision Training of the Paretic Lower Extremity to Enhance Recovery of Locomotion Post Stroke: A Hypothesis-driven Perspective. J Nov Physiother Phys Rehabil. 2025; 12(1): 019-023. Available from: 10.17352/2455-5487.000110

Copyright License

© 2025 Alon G. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Maximising locomotor independence following stroke remains a central goal of neurorehabilitation. Traditional manual techniques, while foundational, are insufficient to fully restore locomotion independence. This paper offers an interpretation of published evidence regarding post-stroke rehabilitation and advocates for a construct of hypothesis-driven approach combined with clinical observation that integrates readily accessible, technology-based precision training designed primarily to target the paretic lower extremity. It emphasises using technologies capable of both assessment and collection of objective performance data over time, advocates for individualised intervention derived from each patient’s baseline locomotion measurements and stresses the need for a quantitative, outcome-driven training program aimed at recovering less dependent locomotion ability. The paper proposes a practical definition and description of independent and dependent locomotion and explores common barriers to recovering independence in locomotion post-stroke. It presents the rationale and mechanisms that govern the selection of therapeutic technologies, including functional electrical stimulation (FES), treadmills, and motorised plinth/tables that hypothetically support recovery of locomotion. The proposed novel composition of precision locomotion training and the added value of incorporating effective and efficient hybrid technologies are highlighted as critical to the recovery of locomotion ability in post-stroke rehabilitation.

SAT: Separation Anxiety Test; PICI-C-3: Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews; PHE-Q: Perrotta Human Emotions Questionnaire; CG: Clinical group; Cg: Control group

Background

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, with impaired locomotion being a primary contributor to diminished independence. Despite advances in physical therapy training methods, many rehabilitation programs continue to rely heavily on manual techniques and structured exercises aimed at regaining standing balance and assisted ambulation. Numerous publications report improvements in balance and gains in walking speed and walking distance at the end of training, for example, Ardestani, et al. [1]. Nonetheless, many patients’ locomotor ability remains limited primarily due to significantly impaired control of the paretic lower extremity. Such limited control adversely affects the ability to walk independently, but also stand up or negotiate stairs and curbs without assistance. Maximal recovery of motor control of the paretic lower extremity warrants a paradigm shift toward technology-enhanced precision training [2]. This precision-derived adaptive paradigm leverages technology-based recording of objective data collected from each patient’s locomotion performance. Moreover, using interpretation of published stroke-related results, this paper offers new, hypothetically driven precision training programs constructed and modified based on repeated quantitative performance data. The program focuses specifically on restoring the ability to stand up and sit down, as well as increasing walking distance and walking speed with and without human assistance or assistive devices. Furthermore, the paper advocates for the utilisation of specialised technologies and methods that enable the restoration of movement control of the paretic lower extremity. The success of the proposed paradigm shift is predicated on acceptance of a practical definition of locomotion independence, on identification of available technologies and the rationale for their selection, while hypothetically increasing the likelihood of recovering better control of the paretic lower extremity.

As defined in this paper, independent locomotion encompasses the ability to ambulate without any assistive devices such as orthosis or functional electrical stimulation (FES) or dependence on hand support while walking. Similarly, patients who survived a stroke should be able to perform sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit transitions, loading on both lower extremities from varied seating heights and navigate stairs using a normal step-over-step pattern without assistance. Reliance on hand support or assistive devices during ambulation marks a transition from independence to partial or full dependence on technology or human assistance or both [3]. This dependence may evolve gradually or emerge abruptly, reflecting a loss of locomotor autonomy. Current literature offers only a rough estimate that about 73% of stroke survivors continue to use hand support, while an unspecified number continue to require human assistance to walk [4] More precise data were reported by Wang and colleagues documenting that of 65 patients who were dependent walkers, 33 (51%) remained dependent on assistive devices at 3 months post-rehabilitation [3]. The need to use a cane, quad-cane or hemi-walker is predominantly associated with the aberrant control of both timing and magnitude of activity of the paretic muscles of the lower extremity.

Impaired control of the paretic lower extremity inevitably limits its use during standing up and sitting down [5,6] as well as during negotiation of stairs and curbs [7]. Specifically, Warenczak-Pawlicka and Lewinski [5] used the 30s Chair Stand Test and the Five Times Sit-to-Stand Test to examine the ability of getting up and sitting down. They reported significantly higher errors in positioning the paretic limb while sitting on a chair and a lower average angular velocity of the paretic knee joint compared to the non-paretic limb while getting up from a chair. Overall, stroke survivors needed more time and performed fewer repetitions of getting up and sitting down while loading significantly less on the paretic lower limb compared to the non-paretic limb. The adverse impact of the paretic lower extremity on the ability to ascend and descend stairs step-over-step is rarely mentioned in available publications [8,9].

Rationale supporting paretic lower limb precision training

Technologies for precision training

Among available technologies that can be utilised in precision training of the paretic lower extremity, this review focuses on functional electrical stimulation (FES), motorised treadmills, and motorised plinth/treatment table, all readily available in most inpatient and outpatient clinics. These technologies can provide objective quantification of each patient’s baseline performance of ambulation, standing up-sitting down, as well as ascending-descending stairs. The selection of each technology is guided by current knowledge of the neuromuscular and biomechanical impairments post-stroke that can be reversed by these technologies. Improved clinical outcomes specifically achieved by utilising FES and a treadmill [10] as a hybrid intervention give credence to the construct of achieving improved control of the paretic lower extremity. Nonetheless, interpretation of studies such as those reported by Al Abdulwahab, et al. [10] and Donlin’s group [11] suggests that researchers focused on general rather than individual patients’ precision training methods, thereby may not have maximised the recovery of locomotion independence. To develop a personalised approach to intervention, it is necessary to describe the common impairments listed in Table 1.

A rationale supporting the utilisation of common rehabilitation technologies is constructed through the recognition of the adverse changes incurred in the paretic lower extremity. One systematic review summarised available data on the structural, pathological alterations seen in the paretic side during the first year post-stroke. Common findings included atrophy, loss of muscle force generation, transformation of some type II fibres into type I fibres, decrease in fibre diameter, apparent myofilament disorganisation, decrease in the number and activity of motor units and abnormal presence of lipid droplets and glycogen granules in the sub-sarcolemmal region [12]. Other investigators found significantly smaller, atrophic muscle mass of the ankle plantarflexors and dorsiflexors, and markedly reduced ability to generate ankle joint torques (moments). Changes in fascicle length, muscle thickness and pennation angle of the paretic plantar flexors were likewise reported [13]. Similarly, the ankle joint’s range of motion on the paretic side was significantly reduced, particularly the dorsiflexion range. Furthermore, the plantar flexors’ fascia thickness was reportedly clearly greater, indicating shortening of the connective tissues [14]. Some of the aforementioned pathophysiological changes have been reversed by applying functional electrical stimulation (FES) to the paretic lower extremity [15,16].

The pros and cons of FES

Among the primary advantages of FES is the ability to induce contraction of paretic muscles better than all other currently available technologies. Specifically, FES can induce isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions, all needed during locomotion. Additionally, FES is likely to enhance peripheral arterial, venous, and lymphatic circulation, while concurrently modulating peripheral, spinal, and brain neural connectivity [15,17-19]. Furthermore, FES can be incorporated and synchronised with other technologies, including treadmills, robotics, and immersive gaming systems [18] throughout the continuum of training, including the home environment. During training, FES should be applied to induce contraction primarily of the dorsiflexors, plantarflexors and hamstrings during walking and to the plantarflexors, quadriceps, and dorsiflexors when standing up and sitting down [6] or when going up and down the stairs (Table 2).

The most notable disadvantages are the currently very high cost of the more advanced wireless wearable FES systems, the need to frequently replace the electrodes and repositioning them correctly, particularly during home use. The limited confidence of clinicians in how, when and why to apply FES in clinical practice has been documented [20].

The pros and cons of treadmills

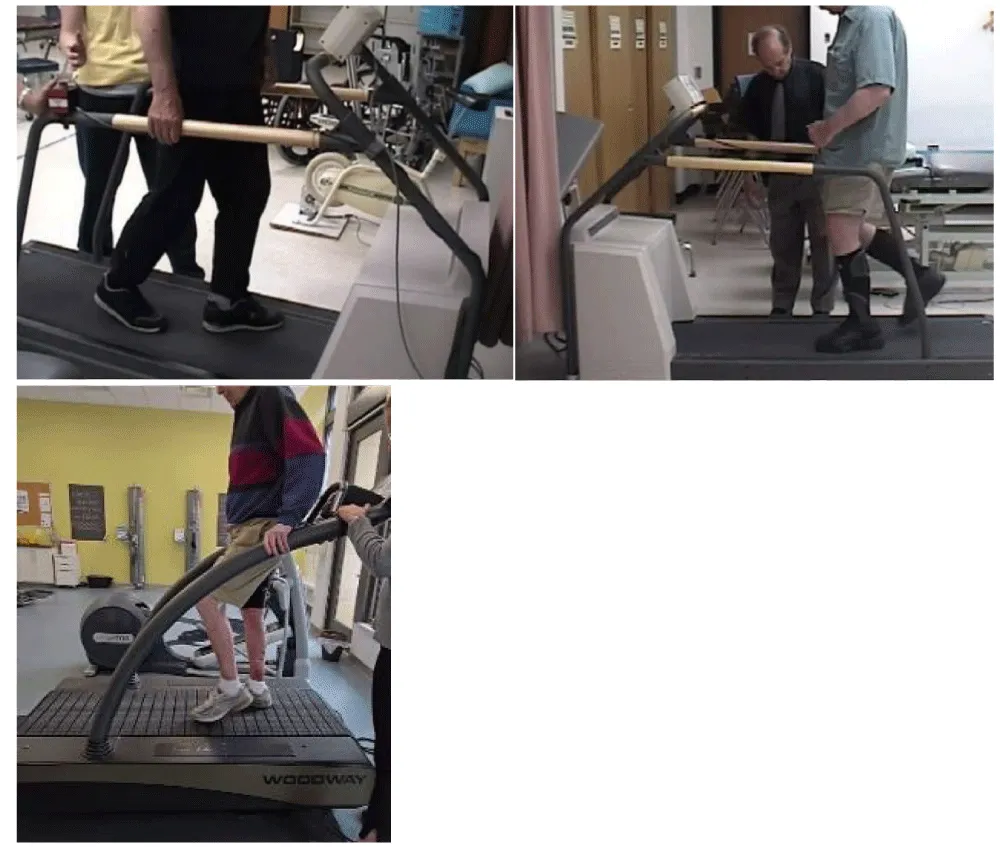

Many stroke survivors using a cane, ankle foot orthosis (AFO), or both walk at a very slow speed ranging between 0.15 to 0.4 meters/sec. Following training, including using treadmills or FES, they may improve speed only modestly by 10-20%. This limited success may be attributed to the legacy approach of using a treadmill to promote cardio-pulmonary fitness, not necessarily improving walking speed [1,21]. It is well known that the faster stroke survivors can walk, the more independent community walkers they likely to be at 6-month post stroke [22] and less dependent on hand support or AFO. Accordingly, using a treadmill to maximise recovery of walking speed requires a different training program. This program is tailored for patients wishing to walk in the community without hand support, and it is based on the author’s many years of utilising it clinically. Using a novel proposed training construct, the patient attempts to walk on the treadmill at the lowest speed while not holding the handrail for 1 minute. If able to walk without holding the handrail (recorded as baseline speed), the treadmill speed is increased by 0.1 mile/hour, and the patient is trained to walk without hand holding at the new speed. As illustrated in Figure 1, only a 5-10-minute training session once a week may result in a dramatic increase in walking speed without hand support. It is noteworthy that the discussed program is hypothetical and not supported by objective clinical evidence of efficacy at this time. Another major advantage is the ability to improve walking and upright balance by training stroke survivors to walk backwards [23].

The main disadvantage of the proposed precision speed training is the required clinician supervision to ensure the safety of the patient, which confines the training to a clinical setting, thus adding to the cost of care.

The pros and cons of an electrically powered plinth or treatment table

Using an electrically powered plinth/treatment table to train stroke survivors could not be found in scientific publication. Yet, these technologies could be particularly useful for training a stroke survivor to stand up and sit down independently. Common biomechanical knowledge informs that the higher the chair’s seat from the floor (measured in cm or inches), the easier it is to stand up and sit down without assistance. In the absence of a motorised plinth or table, many stroke survivors depend on assistance from a clinician or caregiver to be able to stand up. Conceptually, having a height-adjustable training plinth can quantify the baseline height from which each patient is able to stand up independently without assistance while loading equally on both lower limbs, and begin training standing and sitting from that height. Once capable of independently completing the 30s chair stand test or the five-time sit-to-stand test [5], the height is decreased by 2.5 - 5 cm (1-2 inches), and training at the lower height continues until, over time, the patient hopefully can stand and sit independently from a standard height chair (45 cm, 18 inches). The efficacy of the training program remains clinically hypothetical and untested.

One caveat is the diminished loading on the paretic lower extremity while standing up and sitting down [6]. To enable more loading on the paretic side, the training is modified to limit the loading on the non-paretic limb as illustrated in Figure 2. In addition to having a motorised plinth/treatment table only in a clinical setting, the main disadvantage is the required clinician’s supervision to ensure the safety of the patient, which confines the training to a clinical setting, thus adding to the cost of care.

Pros and cons of using unpublished precision training termed “the wall exercises”

Precision training using a house wall is a novel, hypothetical, non-technology approach to uniquely address the inability of many stroke survivors to perform a single-leg stand on the paretic lower extremity. The typical impairments leading to such inability include diminished ability to generate adequate muscle force, particularly of the plantarflexors, limited ankle dorsiflexion range of motion needed to step forward with the non-paretic leg during walking, and the aberrant control of motor synergy among the flexors, extensors, evertors and invertors, including slower reaction time. As illustrated in Figure 3, the training program can be practised in the clinic or in the home environment several times every day, potentially increasing the training dose and the likelihood of regaining the ability of unassisted single limb stance on the paretic limb, minimising walking asymmetry and hypothetically may reduce the chance of falls during ambulation. Table 3 offers a training template for these exercises.

While novel, some clinicians have incorporated such “wall exercises” in practice without any known published objective evidence of efficacy. Not having documented evidence renders the program hypothetical and challenges researchers and clinicians to test this novel intervention.

Summary

Recovering independence in locomotion post-stroke is likely a goal of many stroke survivors. The offered training program in this paper is based on “between the lines” interpretation of multiple published studies using FES, treadmills, and other post-stroke interventions, leading to a tentative hypothesis that researchers and clinicians have not focused specifically on the paretic lower extremity. Furthermore, specific training programs to learn to stand up and sit down independently using the paretic lower extremity, or how to maximise recovery of walking speed, appear to be missing in published clinical literature. This interpretive paper is a call for action to test the hypothesis that a precision training program focusing primarily on minimising the known post-stroke impairments and construct a training program to recover control of the paretic lower extremity during walking, standing and stairs negotiation. If the program proves efficacious, it may lead to markedly less dependent locomotion ability.

- Ardestani MM, Henderson CE, Mahtani G, Connolly M, Hornby TG. Locomotor kinematics and kinetics following high-intensity stepping training in variable contexts poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34(7):652–660. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1545968320929675

- Alon G. A new paradigm is needed to guide the utility of functional electrical stimulation in rehabilitation medicine. J Nov Physiother Phys Rehabil. 2020;7:045–049. Available from: https://www.medsciencegroup.us/articles/JNPPR-7-178.pdf

- Wang CY, Chen YC, Wang CH. Postural maintenance is associated with walking ability in people receiving acute rehabilitation after a stroke. Phys Ther. 2022;102(4). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/102/4/pzab309/6553216

- Peltonen J, Benson S, Kraushaar J, Wunder S, Mang C. Stroke survivors with limited walking ability have unique barriers and facilitators to physical activity. Disabil Rehabil. 2025;47(18):4664–4672. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.1080/09638288.2025.2453639

- Warenczak-Pawlicka A, Lisinski P. Why is it worth carefully assessing the way hemiplegic patients sit and stand up? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26(1):563. Available from: https://bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12891-025-08833-3

- Hou M, He J, Liu D, Guo C, Ma Y. Lower limb joint reaction forces during sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit movements in stroke patients with spastic hemiplegia. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2025;80:102969. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1050641124001511

- Chandler EA, Stone T, Pomeroy VM, Clark AB, Kerr A, Rowe P, et al. Investigating the relationships between three important functional tasks early after stroke: movement characteristics of sit-to-stand, sit-to-walk, and walking. Front Neurol. 2021;12:660383. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.660383

- Flansbjer UB, Downham D, Lexell J. Knee muscle strength, gait performance, and perceived participation after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(7):974–980. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999306002993

- Kim CM, Eng JJ. The relationship of lower-extremity muscle torque to locomotor performance in people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2003;83(1):49–57. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12495412/

- AlAbdulwahab SS, Aldhaferi AS, Alsubiheen AM, Alharbi SH, Alotaibi FH, Alghamdi MA, et al. The effects of functional electrical stimulation of hip abductor and tibialis anterior muscles on standing and gait characteristics in patients with stroke. J Clin Med. 2025;14(7). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/14/7/2309

- Donlin MC, Higginson JS. We will, we will shock you: adaptive versus conventional functional electrical stimulation in individuals post-stroke. J Biomech Eng. 2024;146(12). Available from: https://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/biomechanical/article/146/12/121005/1202831

- Aze OD, Ojardias E, Akplogan B, Giraux P, Calmels P. Structural and pathophysiological muscle changes up to one year after post-stroke hemiplegia: a systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2023;59(4):474–487. Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/europa-medicophysica/article.php?cod=R33Y2023N04A0474

- Wang R, Zhang L, Jalo H, Tarassova O, Pennati GV, Arndt A. Individualised muscle architecture and contractile properties of ankle plantarflexors and dorsiflexors in post-stroke individuals. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1453604. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1453604

- Choi J, Do Y, Lee H. Ultrasound imaging comparison of crural fascia thickness and muscle stiffness in stroke patients with spasticity. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(22). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/14/22/2606

- Narvaez G, Apaflo J, Wagler A, McAinch A, Bajpeyi S. The additive effect of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and resistance training on muscle mass and strength. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2025. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00421-024-05700-2

- Berenpas F, Weerdesteyn V, Geurts AC, van Alfen N. Long-term use of implanted peroneal functional electrical stimulation for stroke-affected gait: the effects on muscle and motor nerve. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2019;16(1):86. Available from: https://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-019-0556-2

- Tang J, Xi X, Wang T, Li L, Yang J. Evaluation of the impacts of neuromuscular electrical stimulation based on cortico-muscular-cortical functional network. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2025;265:108735. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169260725000415

- de Seta V, Romeni S. Multimodal closed-loop strategies for gait recovery after spinal cord injury and stroke via the integration of robotics and neuromodulation. Front Neurosci. 2025;19:1569148. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2025.1569148

- Covarrubias-Escudero F, Appelgren-Gonzalez JP, Nunez-Saavedra G, Urrea-Baeza D, Varas-Diaz G. Enhancing gait biomechanics in persons with stroke: the role of functional electrical stimulation on step-to-step transition. Physiother Res Int. 2025;30(3):e70080. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pri.70080

- Brown L, Street T, Adonis A, Johnston TE, Ferrante S, Burridge JH, et al. Implementing functional electrical stimulation clinical practice guidelines to support mobility: a stakeholder consultation. Front Rehabil Sci. 2023;4:1062356. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2023.1062356

- Hornby TG, Plawecki A, Lotter JK, Shoger LH, Voigtmann CJ, Inks E, et al. Acute intermittent hypoxia with high-intensity gait training in chronic stroke: a phase II randomised crossover trial. Stroke. 2024;55(7):1748–1757. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.124.047261

- Rosa MC, Marques A, Demain S, Metcalf CD. Fast gait speed and self-perceived balance as valid predictors and discriminators of independent community walking at 6 months post-stroke: a preliminary study. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(2):129–134. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/10.3109/09638288.2014.911969

- Awosika OO, Drury C, Garver A, Boyne P, Sucharew HJ, Wasik E, et al. Characterizing the longitudinal impact of backwards locomotor treadmill training on walking and balance outcomes in chronic stroke survivors: a randomized single-center clinical trial. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2024. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.09.11.24313519

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley