Journal of Novel Physiotherapy and Physical Rehabilitation

Exercise-induced time-dependent changes in plasma BDNF levels in people with schizophrenia

Laira Fuhr1, Caroline Lavratti1, Ivy Reichert Vital da Silva1, Gustavo Pereira Reinaldo2, Nathan Ono de Carvalho1, Jordana Lectzow de Oliveira1, Luciane Carniel Wagner1, Jerri Ribeiro1 and Viviane Rostirola Elsner1*

2Postgraduate Program in Health Sciences, Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre, RS – Brazil

Cite this as

Fuhr L, Lavratti C, da Silva IRV, Reinaldo GP, de Carvalho NO, et al. (2018) Exercise-induced time-dependent changes in plasma BDNF levels in people with schizophrenia. J Nov Physiother Phys Rehabil 5(1): 001-006. DOI: 10.17352/2455-5487.000056Objective: To investigate the short and long-term outcomes of a concurrent exercise protocol (CEP) on plasma Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and the effect of this intervention in the self-esteem and mental health in people with schizophrenia (SZ).

Methods: In this quasi-experimental study, 15 participants underwent a structured, supervised and group based CEP for 12 weeks (the sessions were performed 3 times a week for 60 minutes). In order to verify the short- and long-term effects of exercise on BDNF levels, blood samples of 15 ml were collected pre-intervention and on the 4th, 8th and 12th week(s) after intervention started. To evaluate self-esteem, the Rosemberg Self-esteem Scale was used, and the general mental health status was measured through the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12). Both questionnaires were applied before and after intervention.

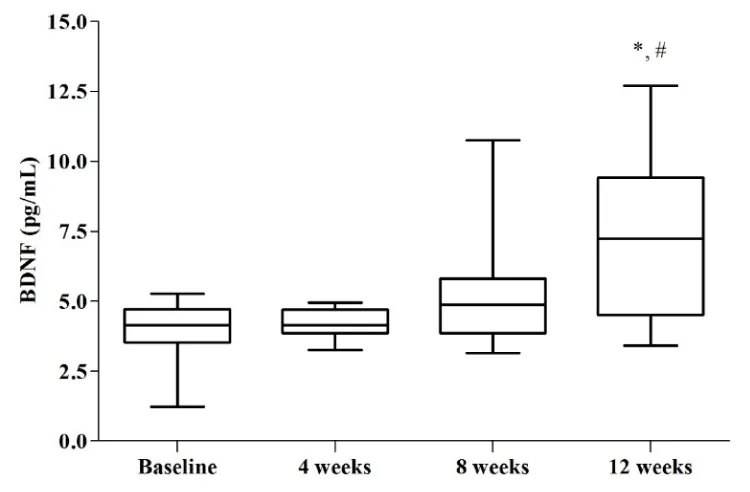

Results: BDNF plasma levels increased significantly at the 12 th week(s) when compared to baseline and in 4 weeks periods. There were no observed changes on self-esteem neither a trend of improvement in the GHQ at the post-intervention phase when compared to the baseline. Finally, the CEP reduced significantly anthropometric variables.

Conclusion: The CEP induced time-dependent modulation on BDNF levels in individuals with SZ, increasing its levels only in a long-term period.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a severe mental illness which usually starts at a young age [1] and is characterized by abnormalities in the perception or expression of reality with a lifetime prevalence ranging from 1% to 6.6% [2–4]. Although its physiopathology is unknown, recently discovered evidences suggest that reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been implicated [5,6], in SZ. BDNF is a neurotrophin essential in promoting synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, cell survival, neuronal growth and maturation [7]. Furthermore, it is also associated with mood, emotion and memory/ learning processes [8]. This neurotrophin is able to cross the blood-brain barrier in a bi-directional manner and therefore the blood levels of BDNF may reflect the brain levels of this neurotrophin and vice-versa [9]. In view of these considerations, peripheral BDNF levels have been used as a biomarker in clinical investigations [10].

Patients with SZ display poorer health behaviors [11] as well as demonstrate remarkable neurocognitive impairments including reduced functioning [3,12] and deficits in working memory and verbal learning when compared to the general population [13]. It should be emphasized that some of these individuals have low self-esteem, which may be associated with poor acceptance of the disease and is related to the development of depression [14].

A sedentary life-style is commonly observed in persons with SZ [15], which contributes to the increased prevalence of co-morbid illnesses, such as, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension and respiratory diseases [16,17]. On the other hand, exercise has been pointed out as an interesting accessory to therapeutic strategies in SZ treatment, resulting in beneficial impacts to both physical and mental health [18–20]. Symptoms in SZ such as low self-esteem and social withdrawal have been demonstrated to be alleviated following exercise sessions [21]. In fact, some evidences suggest that BDNF may mediate, at least in part, these beneficial effects [22,23].

It is important to highlight that BDNF up-regulation/release in response to exercise is influenced by several factors such as modality, intensity, duration and volume of the exercise session [24,25]. In spite of this knowledge, the time window of BDNF modulation following exercise in individuals with SZ has not been sufficiently explored, making this a research topic that is particularly relevant.

Additionally, the majority of the studies regarding the impact of exercise in people with SZ used aerobic and/or resistance programs, while less attention has been devoted to concurrent protocols. This modality is characterized by the combination of endurance and resistance exercises in the same session and showed to improve health-related markers in this population [26,27]. However, there are no reports demonstrating the effect of a concurrent exercise protocol on self-esteem and mental health in persons with SZ.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were (1) to examine the short and long-term outcomes of a concurrent exercise protocol on plasma BDNF levels and (2) the impact of a concurrent exercise protocol during 12 weeks in the self-esteem and mental health in persons with SZ.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-five individuals diagnosed as having SZ of both genders were invited to participate in this quasi-experimental study. All participants were recruited at the Associação Gaúcha de Familiares de Pacientes Esquizofrênicos (AGAFAPE).

The study procedures were submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the Methodist University Center-IPA and approved under protocol number 1.243.680/2015. After a detailed description of the study’s objectives and procedures, informed consent forms were obtained from all interested participants.

Inclusion criteria were subjects with a DSM-V diagnosis of schizophrenia, aged 18-50 years-old, who were undergoing medical treatment, participants of AGAFAPE, not to be in a psychotic crisis, not to be ingesting alcohol and/or recreational drugs. Subjects were eligible if they had not engaged in any exercise programs in the past six months. The exclusion criteria included the presence of musculoskeletal and joint disorders that made it difficult to carry out physical exercise as well as any individuals with a history of autoimmune diseases; cancer and/or cardiovascular complications and/or having any medical contraindications.

Intervention

The intervention was characterized by a group-based program and it took place on Mondays, Wednesday and Fridays. Always at the same time of the day (between 2 P.M. and 3 P.M.), for 12 consecutive weeks. This period was chosen based on previous studies that show beneficial effects on SZ patients after a 12 week exercise intervention period [22,28]. Each session lasted approximately 1 hour and was monitored and supervised by an exercise physiologist to ensure the safety of each participant.

The concurrent exercise protocol used in this study followed the recommendations of the American College of Sports Medicine [29]. Initially, the participants underwent a week of adaptation characterized by the exercises described below, at a low intensity corresponding to 40% effort of the maximum cardiorespiratory capacity which was controlled using the Scale of Perceived Exertion (Borg). The adaptation week’s intention was to instruct the correct technique of performing the exercises to the patients. The other sessions were divided into four different exercise periods. An initial warming-up period of five minutes, a localized muscular resistance exercises period of thirty minutes, an aerobic exercise walk period of twenty minutes and finishing with a stretching period of five minutes.

The exercises performed sought to understand the major muscle groups involved in aerobic and resistance exercises. The exercises used were: squats without weights, biceps curls, shoulder lateral raise, plantar flexion, hip abduction, knee extension, back extension, abdominals curls and a twenty minutes walk as mentioned above. For each exercise, there were three sets of fifteen repetitions each. The intensity was controlled over the range of 10-11 through the Scale of Perceived Exetertion (Borg), which was used to add weights to the exercises, adjusted to maintain the maximum strain in 15 repetitions as well as the speed of walking in order to keep effort at 60% of maximal cardiorespiratory capacity (12-13 at Borg Rating). Adherence/frequency to the intervention was measured by attendance in each session.

The participants were requested not to make changes to their regular diet during the intervention, since the main goal of the study was to only analyse the effects of exercise practice on the outcomes outlined below.

Assessments

In order to examine the short(-) and long-term effects of the concurrent exercise program on plasma BDNF levels, blood samples of 15ml were taken in the antecubital region of the participants at different time-points: before the exercise program and on the 4th, 8th and 12th week after the intervention started. Self-esteem and mental health were assessed at baseline and on the 12th week(s) after the concurrent exercise protocol.

Blood sampling and BDNF assay: Histopaque® (Sigma-Aldrich 1077) was added into the collected sample in a 1:1 proportion in a conical tube and then centrifugation was held at 1500 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. Afterwards, the “buffer coat” was removed from the portion between plasma and Histopaque®. The plasma was collected and stored in conical tubes of 1.5 ml, at -80°C, for later determination of BDNF levels. Plasma BDNF levels were determined with the ELISA method, from Sigma-Aldrich commercial kit (catalog number RAB0026) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the sample and BDNF specific standards were added to ELISA microplate and incubated for 2.5 hours at room temperature. Subsequently, the solutions were discarded and the same plate was washed 4 times with wash buffer (PBS, Tween 20 0.01%). After washing, the secondary antibody bound to biotin was added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation. The plate was again washed with wash buffer and streptavidin solution was added and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes with gentle agitation. The solution was discarded and the plate put through the washing process. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added, and then it was incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, in light deprivation, with gentle agitation. The stop solution was added and the plate was read in a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 450nm. The plasma BDNF levels were expressed as ng/ml.

Self-esteem analysis: Self-esteem was assessed through the application of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [30], an instrument that proposes a one-dimensional measure with ten items designed to evaluate the positive or negative attitude of the individuals in relation to themselves. The sum of the responses to the 10 items gives the scale score, the total ranges from 10 to 40. A high score reflects a high self-esteem. It is an easily understood, Likert-type self-applied scale (eg: I think I have several good qualities: (1) I totally disagree (2) disagree (3) agree (4) totally agree. It was adapted and validated in Brazilian Portuguese and has been used extensively in Brazil, where studies demonstrate its reliability for use in different populations [31,32].

Mental health analysis: For the assessment of general mental health we used The General Health Questionnaire -12 (GHQ-12), an instrument developed to identify psychiatric symptoms such as depression or anxiety, occurred in the two weeks preceding the application [33]. It does not aim to diagnose pathologies, but to screen for possible cases. Originally containing 64 questions, the instrument also features several reduced versions. In the present study, we used the 12-item version, validated in Brazil [34]. As it is a Lickert-type scale with four alternatives (Ex: Have you felt unhappy and depressed: 1) No; 2) As usual; 3) More than usual; 4) Much more than usual), for the analysis of the data the scale was dichotomized (alternatives 1 and 2 indicated no problem, 3 and 4, presence.) (Higher scores indicate a higher prevalence of symptoms.

Statistical analysis

After the normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and variance (Levene’s) tests, anthropometric, self-esteem and mental health data, before and after training were considered parametric and then analyzed using paired Student t-test (presented as mean ± standard deviation). ANOVA for repeated measures followed by a post-hoc Bonferroni was applied to evaluate BDNF levels (non-parametric data) at the different time-points: basal, 4th, 8th, 12th week(s) (presented in median with interquartile range). Significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05 and SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 highlights basic demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Of the 25 individuals recruited at baseline for the study, 10 were excluded for not agreeing to perform blood collection. During the program, no participants withdrew and therefore 15 individuals successfully completed the 12-weeks intervention period. Training session attendance was highly consistent (~97%). Furthermore, 12 weeks of the concurrent exercise protocol were able to improve anthropometric measurements in participants (Table 2).

BDNF Levels at different time-points

As shown in Figure 1, there was a remarkable increase on BDNF levels at the 12th week period when compared to the basal (p=0.006) and 4th week (p=0.007) periods.

Self-esteem and mental health

The concurrent exercise protocol did not affect Self-esteem and Mental Health in the participants, as described in table 2.

Discussion

After 12(-) weeks of intervention, the participants exhibited substantially higher plasma BDNF levels when compared with the baseline and 4th week(s) periods. Our data corroborates those obtained by Kim and colleagues[35] who reported increased BDNF values in persons with SZ in response to a concurrent exercise protocol with similar design than the present study (3 days per week during 12 weeks, 60 minutes each session). On the other hand, it was previously shown that 10 and 20 weeks (twice a week) of a concurrent exercise program did not alter BDNF levels in persons with SZ [27]. Altogether, these findings led us to hypothesize that BDNF modulation in response to concurrent exercise exposure in individuals with SZ depends on the weekly training frequency, specifically, 3 sessions per week are necessary to promote significant increases in this biomarker.

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that single bouts of or short-duration exercise protocols are able to induce significant enhancement on BDNF levels in both healthy and psychiatric patients, as well as in persons with bipolar disorder [10,36,37]. Thus, failing to observe BDNF modulation after 4 weeks of intervention in the current study is unexpected. We might suggest that the modulation of BDNF in response to this physical exercise modality, in persons with SZ, occurs in a time-dependent manner, requiring long-term exposure.

Recent experimental and clinical evidences have demonstrated that BDNF plays a pivotal role on energy homeostasis, eating behavior, regulation of appetite, and weight regulation/reduction [23,38–41]. Our data can be related to these studies, since in combination to BDNF enhancement, SZ individuals showed an improvement in body composition (including body mass and BMI decrease) after a 12 week program of concurrent exercise. In accordance, Kim and colleagues [35] reported that a concurrent exercise intervention during 12 weeks, three days per week, increased BDNF levels and also reduced anthropometric variables in persons with SZ. Altogether, these findings support the idea regarding the protective effects of BDNF in the metabolism of this population, which could be improved with long-term exercise practice.

It has been widely reported that different physical exercise programs are able to improve self-esteem in persons with SZ [42,43]. To our knowledge, this study has described for the first time the impact of a concurrent exercise protocol in this variable. Surprisingly, no difference in self-esteem was observed after the intervention, which might be explained by the stable situation of this group of subjects. This stability was supported by the test results in which the subjects scored “medium” on self-esteem. That is, within a normal range. These scores were recorded before the SZ patients started the program and at the end of it . We believe that their participation in an association of people with schizophrenia (AGAFAPE) reinforces their self-esteem. At this association, they routinely receive and share information about their disease, socialize, exchange support and especially are free from the stigma and prejudice often present in other (places. Belonging to this group represents a major boost of self-esteem and personal empowerment of those individuals.

Although the GHQ-12 is an important instrument developed to identify psychiatric symptoms, its application, until the present moment, has never been used in studies conducted with persons with SZ who were submitted to exercise programs. We found a tendency of improvement after the intervention, which suggests that this type of program can favor the well-being of these people, reducing general symptoms of anxiety and depression. Our findings corroborate other studies that indicate physical exercise(s) may decrease psychiatric symptoms in this population [27,43].

Finally, another remarkable point to discuss was the adherence of the participants to the program, since there were no withdrawals. One possible explanation for this positive response of the participants could be the intervention profile, which was characterized by structured, supervised and group based exercise programs that seems to be more attractive for them when compared to non-structured and non-group based, as previously reported [26,44,45].

A limitation of the current study is the quasi-experimental design, which does not include a control group. Further investigations should be done with a more robust number of participants, which could enable us to assess other criteria, such as the possible influence of the use of medication, age and gender in response to exercise modulation on BDNF levels in persons with SZ.

Summarizing, this study demonstrated that a concurrent exercise program induced higher levels of BDNF and contributed to improve(s) anthropometric measurements in persons with SZ. These findings reinforce that exercise might be considered an effective, low-cost, therapeutic strategy to regulate (these individuals through regulating) BDNF levels. Exercise acts in a time-dependent manner, it’s benefits are more evident the longer the subject is exposed to it.

This work was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS)/Brazil. We also thank AGAFAPE for their receptiveness and collaboration.

- Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC (1996) Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 1022–1031.Link: https://goo.gl/kUZ1m2

- Moreno DH, Andrade LH (2005) The lifetime prevalence, health services utilization and risk of suicide of bipolar spectrum subjects, including subthreshold categories in the São Paulo ECA study. J Affect Disord 87: 231–241. Link: https://goo.gl/3GMrgy

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, et al. (2007) Kessler, Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 543–52. Link: https://goo.gl/iCSEhV

- Freedman R (2003] Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 349: 1738–1749. Link: https://goo.gl/fvYrr2

- Green MJ, Matheson SL, Shepherd A, Weickert CS, Carr VJ (2011) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in schizophrenia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 16: 960–972. Link: https://goo.gl/Kz7gb1

- Autry AE, Monteggia LM (2012) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev 64: 238–58. Link: https://goo.gl/Dx9rjv

- Poo MM (2001) Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 24–32. Link: https://goo.gl/vN8rsJ

- Binder DK, Scharfman HE (2004) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors 22: 123–31. Link: https://goo.gl/L9nLYz

- Pan W, Banks WA, Fasold MB, Bluth J, Kastin AJ (1998) Transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor across the blood-brain barrier. Neuropharmacology 37: 1553–1561. Link: https://goo.gl/3UC2RE

- Schuch FB, da Silveira LE, de Zeni TC, da Silva DP, Wollenhaupt-Aguiar B, et al. (2015) Effects of a single bout of maximal aerobic exercise on BDNF in bipolar disorder: A gender-based response. Psychiatry Res 229: 57–62. Link: https://goo.gl/EnpA9U

- Roick C, Fritz-Wieacker A, Matschinger H, Heider D, Schindler J, et al. (2007) Health habits of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42 268–276. Link: https://goo.gl/M7h1Es

- Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK (2004) Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res 72: 41–51. Link: https://goo.gl/NLg8Re

- Christopher R Bowie and Philip D Harvey (2006) Cognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia, Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2: 531–536. Link: https://goo.gl/qYdnps

- Aaron T. Beck, Neil A. Rector, Neal Stolar, and Paul Grant (2009) A review of Schizophrenia: Cognitive Theory, Research, and Therapy. Cogn Behav Ther B Rev 5: Link: https://goo.gl/TCqv8y

- Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Bartels MN, Armstrong HF, Ballon JS, et al. (2014) Aerobic fitness and body mass index in individuals with schizophrenia: Implications for neurocognition and daily functioning. Psychiatry Res 220: 784–791. Link: https://goo.gl/attRxe

- Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, Blumenthal JA, Fabricatore AN, et al. (2009) Alpert, Obesity Among Those with Mental Disorders. Am J Prev Med 36: 341–350. Link: https://goo.gl/NmdpDh

- Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Islam A, King MB (2007) Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom’s General Practice Rsearch Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 242–249. Link: https://goo.gl/mo2KhX

- Firth J, Stubbs B, Rosenbaum S, Vancampfort D, Malchow B, et al. (2016) Aerobic Exercise Improves Cognitive Functioning in People With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr Bull sbw115. Link: https://goo.gl/ksnk3s

- Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Wampers M, et al. (2015) Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 14: 339–347. Link: https://goo.gl/2Uck3u

- Stubbs B, Ku PW, Chung MS, Chen LJ (2016) Relationship Between Objectively Measured Sedentary Behavior and Cognitive Performance in Patients With Schizophrenia Vs Controls. Schizophr Bull sbw126. Link: https://goo.gl/jiZtp2

- Faulkner GA. Taylor (2005) Exercise, health and mental health: Emerging relationships. Taylor & Francis, New York. Link: https://goo.gl/oYXJTy

- Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Bartels MN, Armstrong HF, Ballon JS (2015) The impact of aerobic exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurocognition in individuals with schizophrenia: A single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Bull 41: 859–868. Link: https://goo.gl/xVhMwp

- Kuo FC, Lee CH, Hsieh CH, Kuo P, Chen YC, Hung YJ (2013) Lifestyle modification and behavior therapy effectively reduce body weight and increase serum level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in obese non-diabetic patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 209: 150–154. Link: https://goo.gl/xbwvEV

- Rasmussen P, Brassard P, Adser H, Pedersen MV, Leick L, et al. (2009) Pilegaard, Evidence for a release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from the brain during exercise. Exp Physiol 94: 1062–1069. Link: https://goo.gl/Bm4Fmn

- Ferris LT, Williams JS, Shen CL (2007) The Effect of Acute Exercise on Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels and Cognitive Function. Med Sci Sport Exerc 39: 728–734. Link: https://goo.gl/fetjhd

- Marzolini S, Jensen BP (2009) Melville, Feasibility and effects of a group-based resistance and aerobic exercise program for individuals with severe schizophrenia: A multidisciplinary approach. Ment Health Phys Act 2: 29–36. Link: https://goo.gl/t9jk6Y

- Silva BA, Cassilhas RC, Attux C, Cordeiro Q, Gadelha AL (2015) A 20-week program of resistance or concurrent exercise improves symptoms of schizophrenia: Results of a blind, randomized controlled trial. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 37: 271–279. Link: https://goo.gl/xhdjQs

- Lavratti C, Dorneles G, Pochmann D, Peres A, Bard A, et al. Elsner, Exercise-induced modulation of histone H4 acetylation status and cytokines levels in patients with schizophrenia. Physiol Behav 168: 84–90. Link: https://goo.gl/15Fo7d

- ACSM, ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 2009. Link: https://goo.gl/wyf62Q

- Rosenberg M (1989) Society and the adolescent self-image. Revised edition, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown. Link: https://goo.gl/xY6VBp

- Avanci JQ, Assis SG, Dos Santos NC, Oliveira RVC (2007) Adaptação tanscultural de escala de auto-estima para adolescents. Psicol Reflexão E Crítica 20: 397–405. Link: https://goo.gl/YZ7Eu7

- Hutz CS, Zanon C (2011) Revisão da apadtação, validação e normatização da escala de autoestima de Rosenberg: Revision of the adaptation, validation, and normatization of the Roserberg self-esteem scale. Avaliação Psicológica 10: 41–49. Link: https://goo.gl/exVdEV

- Goldberg DP, Hillier VF (1979) A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 9: 139–145. Link: https://goo.gl/4QYXmY

- Mari JJ, Williams P (1985) A comparison of the validity of two psychiatric screening questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in Brazil, using Relative Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. Psychol Med 15: 651–659. Link: https://goo.gl/nBwMyo

- Kim HJ, Song BK, So B, Lee O, Song W, et al. (2014) Increase of circulating BDNF levels and its relation to improvement of physical fitness following 12 weeks of combined exercise in chronic patients with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res 220: 792–796. Link: https://goo.gl/bxvMfP

- Erickson KI, Prakash RS, Voss MW, Chaddock L, Heo S, et al. (2010) Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Is Associated with Age-Related Decline in Hippocampal Volume. J Neurosci 30: 5368–5375. Link: https://goo.gl/Mr71w1

- Ströhle A, Stoy M, Graetz B, Scheel M, Wittmann A, et al. (2010) Acute exercise ameliorates reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with panic disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35: 364–368. Link: https://goo.gl/vuqt23

- Xu B, Goulding EH, Zang K, Cepoi D, Cone RD, et al. (2013) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates energy balance downstream of melanocortin-4 receptor. Nat Neurosci. 6: 736–742. Link: https://goo.gl/qnjK38

- Nakagawa T, Tsuchida A, Itakura Y, Nonomura T, Ono M, et al. (2009) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates glucose metabolism by modulating energy balance in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 49: 436 LP-444 Link: https://goo.gl/kVryPu

- Nonomura T, Tsuchida A, Ono-Kishino M, Nakagawa T, Taiji M, et al (2001) Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Regulates Energy Expenditure Through the Central Nervous System in Obese Diabetic Mice. Int J Exp Diabetes Res 2: 201–209. Link: https://goo.gl/fzQLqg

- Zhang XY, Tan YL, Zhou DF, Cao LY, Wu GY, et al. (2007) Serum BDNF levels and weight gain in schizophrenic patients on long-term treatment with antipsychotics. J Psychiatr Res 41: 997–1004. Link: https://goo.gl/NsFzWy

- Yoon S, Ryu JK, Kim CH, Chang JG, Lee HB, et al. (2016) Preliminary Effectiveness and Sustainability of Group Aerobic Exercise Program in Patients with Schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 204: 644–650. Link: https://goo.gl/PpeQwf

- Soundy A, Roskell C, Stubbs B, Probst M, Vancampfort D (2015) Investigating the benefits of sport participation for individuals with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Psychiatr Danub 27: 2–13. Link: https://goo.gl/i5bAz6

- Hutchinson DS (2005) Structured exercise for persons with serious psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv 56: 353–354. Link: https://goo.gl/KfU4XN

- Archie S, Wilson JH, Osborne S, Hobbs H, McNiven J (2003) Pilot Study: Access to Fitness Facility and Exercise Levels in Olanzapine-Treated Patients. Can J Psychiatry 48: 628–632. Link: https://goo.gl/f7ha2C

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley